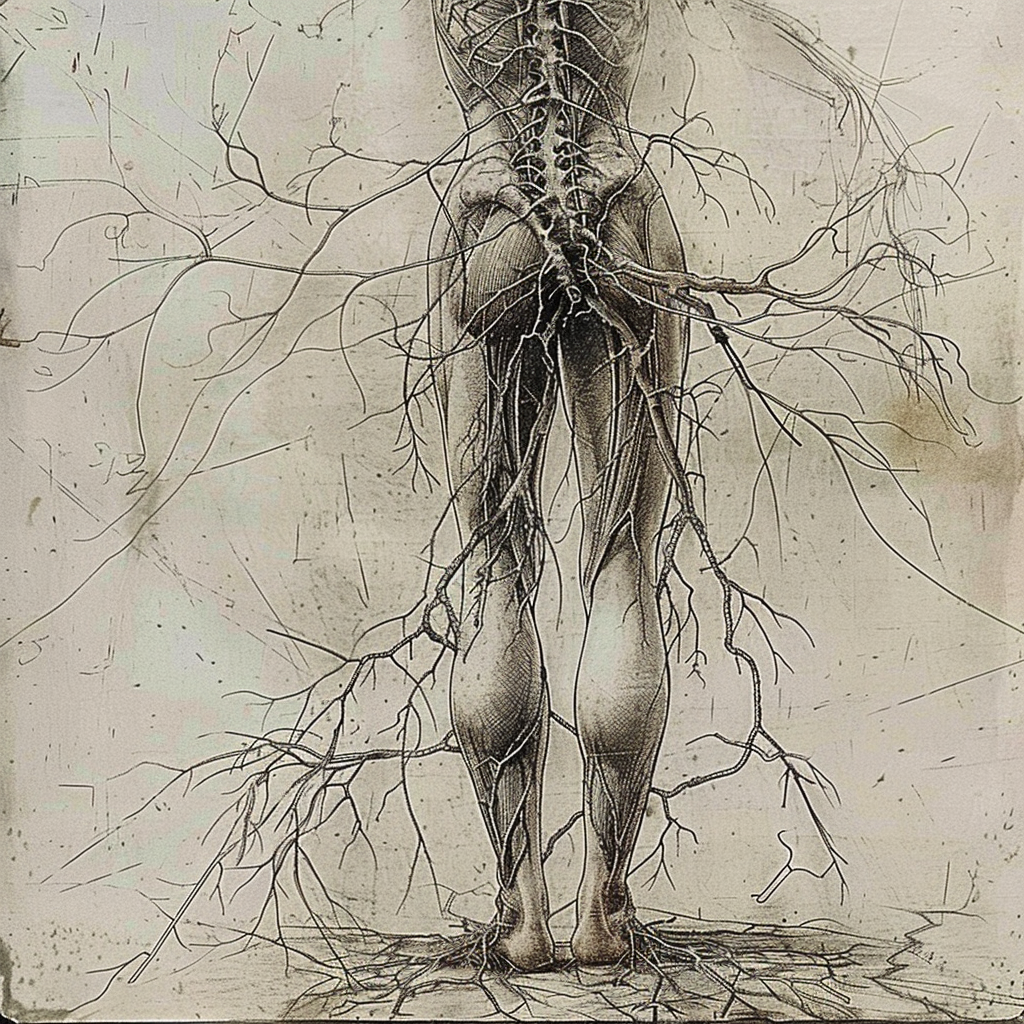

To prolong my ability to walk, I had made it my ritual during my second year in my new home to walk a circle around the property each morning, leaning on two trekking poles for support. This simple discipline became my lifeline to normalcy, a daily affirmation of my diminishing independence. But my relentless disease, in its cold indifference, had other plans.

One frigid morning, in one of the worst cold snaps in memory, my feet betrayed me on a patch of ice. The fall itself was unremarkable. The aftermath was anything but.

As I lay there, the bitter cold of the frozen ground seeping through my clothes, a chilling realization dawned: the strength had finally ebbed from my limbs. My struggles to rise were as futile as they were exhausting. After a half hour of effort, I was still helplessly sprawled at 6:30 AM, miles from the nearest soul, without even the comfort of a cell signal. The 15-degree Fahrenheit air (-9 Celsius) bit at my exposed skin, and with each passing moment, the grim possibility of someone finding my body in frozen mud grew more real.

Resolved not to end as a cautionary tale for the unreasonably stubborn, I fought to flip onto my front. From there, on trembling elbows and knees, I began the agonizing crawl towards a distant woodpile – my only hope for leverage. For 45 excruciating minutes, I inched from one unstable stack to another, my weakened, cold-numbed limbs barely responding to my desperate commands. At last, I found myself upright, leaning heavily on my trekking poles for all the support I could summon.

As I cautiously navigated back to the warmth of the house, each step a victory against gravity, my stubborn mind finally accepted an undeniable truth: I needed help. My falls were becoming more frequent, more dangerous. In the months that followed, my body kept score: a broken right kneecap, a fractured left ankle. Soon, a motorized wheelchair became my constant companion everywhere but the office, where I clung to the illusion of normalcy for my fledgling company by using crutches or a cane to masquerade as someone whose injuries would heal.

This was also the time that I hired help. Mark had been a caregiver for over 15 years for people, often in the final stages of their lives. He came with his own history of struggles: a dysfunctional family, battles with addiction, bouts of homelessness, suicide attempts, rehab, even an apartment struck by a tornado. Yet, he emerged as a deeply compassionate aid for the terminally ill. Mark was a study in contrasts: kind yet temperamental, youthful yet weathered, his thin frame adorned with bold tattoos with recurring motifs of Ravens and Anubis, the dog-headed Egyptian god of the underworld and guardian of the dead.

Acceptance

Despite my best efforts, my strength continued to wane like a tide pulling ever further from shore. By midsummer, the long masquerade of health had become impossible to maintain. The time had come to shed the comforting lies and face the stark truth with those who depended on me. With a heavy heart and trembling fingers, I composed an email to the company, finally breaking the news of my condition.

As I hit ‘send,’ I felt a chapter closing – not just in my career, but in my life. The facade of normalcy crumbled, revealing the vulnerable, mortal man beneath. Yet in that moment of raw honesty, I found an unexpected strength. Acceptance, however painful, was liberating.

The Weight of a Feather

When I first noticed my caregiver’s tattoo of Anubis, the ancient Egyptian guardian of the dead, the symbolism struck me as both profound and perhaps even heavy-handed. Here was a man who would journey with me through this unusually slow descent, bearing the image of a god who protected and guided souls to their final judgment.

In Egyptian lore, Anubis led the deceased to a set of scales where their heart would be weighed against a feather. A heart lighter than the feather meant ascension; a heavier one, oblivion. As I contemplated on the myth, one thought weighed upon my heart with particular gravity: I would never know my grandchildren.

I would not be there to read them bedtime stories, feel the hug of their precious little arms, tuck them in, or whisper, “Goodnight—grandpa loves you.” Instead, I would be an abstraction, a stranger in old photographs taken before they were born, wearing outdated clothes.

This realization sparked an idea. If I couldn’t read to my grandchildren, perhaps I could give them a story of their own. So, brushing off atrophied artistic skills and embracing new technologies to overcome my failing hands, I set out to create a children’s book.

Set in this beautiful valley I now call home, the story features the animals that share this slice of earth with me. It is a retelling of the Zen parable of “The Move,” reimagined as a story explaining how the frogs came to our valley stream every spring. A grandmother deer recounts this wisdom to her spotted grandchildren as they nestle in tall grass for a warm spring nap.

Writing and illustrating became an extension of my daily meditations. Each word written and each image crafted demanded presence and mindfulness. As I worked, I found myself more attuned to the world around me—the rustle of leaves, the calls of birds, the play of light on water. In giving voice to the animals of the valley, I rediscovered my own. I felt my heart grow lighter.

When finished, it became obvious to me that it should be shared outside the audience of my future grandchildren. So, I named it “Ahtu,” the word for “deer” in the native American language of this land, and found a publisher. Now, my bedtime story can be found in bookstores across the country, on Amazon.com, and in all the elementary schools and public libraries of Bucks County.

6 Responses

Besides the book, the grandchildren will have this blog as a memory of the grandfather they never had the chance to meet.

I read most of this word for word, but skipped a few lines here and there.

I saved this one: “…but the fact remained: I was stronger than I would ever be again. So, I committed to doing the most good with my remaining strength until it was gone.” => this echoes my innate sensibility…make the most of what I’ve got; also pace and balance: perseverance furthers. The Tao is my center…since 1972.

Then I stopped to dive into the Zen story, “The Move”. I found a few others. Good stuff.

In 1995, I fell backwards off a climb 20 above a rocky landing. I landed hard. Later, I had a vision and an epiphany, and a neck fusion.

When I was very young, I wanted to have enough, and never too much.

Got it done.

Rich or poor, it’s nice to have money.

Love it that your balance is exquisite, and that being human is your jam.

Thanks for the kind words.

By the way, the children’s book I did that year is a retelling of the Zen story “The Move”.

Having recently lost my best friend of over 60 years to this terrible disease, you gave me insight into her final years that I could only guess at. Her voice was the first thing to go, and frontal lobe dementia took away from her memory a lot of our shared connection. We lived far apart, so the changes to her physical abilities in the 6 months between visits was stark. Thanks for showing me that even in the prison of a failing body, there can be joy and peace and an appreciation for the little things. She did have the benefit of a loving and devoted caregiver in her husband of 55 years. Though she couldn’t speak anymore, and could barely scribble on a small white board, when she was done; when she no longer felt that staying was better than going, she clearly wrote on that board “I quit”, and within minutes she was gone. Only the devastation of losing her remained. My grandchildren are now all young adults, but I will buy your book in both her honor and yours for the great grandchildren I may or may not live to meet.

Beautiful journal entries & legacy for your children & grandchildren. One of dearest friends had ALS, it’s been years since she passed, but, I remember the excruciating stages. It’s the cruelest of diseases. I can think of nothing worse, except the death of a child & last August, I lost both of my daughters, Kelly was 54, died from a asthma induced heart attack. 5 days later, my younger daughter, Kacey, 45, died of a massive heart attack. Neither one had that history. If we could go back in time & I could get ALS, but they could live, I’d gladly do it. But, with disease & death, we have no choice, tomorrow is not guaranteed & growing older is a privilege not everyone gets. I know I’ll see my girls again. That’s God’s promise. I live for that! Wishing you God’s peace & comfort.

Thank you for your kind words and you have all my compassion for your suffering. Please do read on from here. The order doesn’t matter and it’s my sincere hope that some of what I’ve written helps.